There are many times in life when an idea strikes while the electricity is out, and your hand is already cramping from living out of old pickle jars due to spoilage in the fridge. Most writers are ill-prepared to deal with this situation. I admit, for years, I was one of them. But no more.

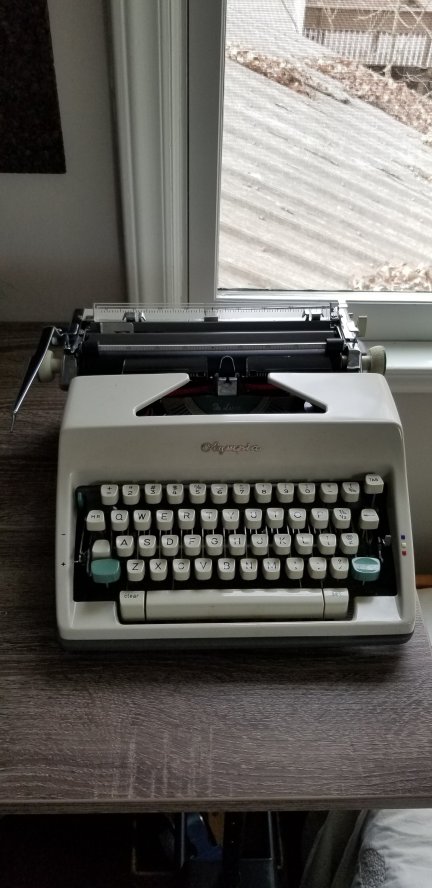

I’m now the proud owner of an Olympia SM-9 manual typewriter. For the kids, “manual” means it’s a hand-operated machine that requires no plug, no battery, no power source other than stiff fingers. (A “typewriter” is a metal object that imitates some of the functions of Microsoft Word by printing directly onto a sheet of paper, one letter at a time.) Apparently I missed the boat on these suckers—a few years back they could be had in decent condition for a pittance at a Goodwill store. Now if you want a fully refurbished machine, you’re looking at several hundred, and more if it’s collectible.

Luckily, the Olympia SM-9 falls on the lower end of the spectrum due to what I might call German aesthetic sensibilities. My 1965 model seems to have been designed shortly after “vintage” ceased to mean “cool”. It may have been the inspiration for early desktop computers. But what she lacks in style, she more than compensates for in grace. This model is arguably the finest feat of engineering in over 100 years of manual typewriting history. They were made in West Germany during the years that forged that nation’s reputation for mechanical marvels. It’s a tank on a semi-portable frame. Every little detail of the function is butter-smooth and bulletproof.

I grew up working on electric typewriters, so these aren’t entirely foreign to me, but I can’t help but feel awed that a machine can operate so precisely, printing perfectly aligned letters at lightning speed from a moving carriage for over 60 years, without the need for a plug. I think I came to associate technology with complexity, and especially with wires, microchips, and software updates. But men used to build some pretty impressive things that moved how and to what rhythm a human being orchestrated.

So what’s it for? I truly don’t know yet, other than the creeping feeling that there are no such marvels being produced anymore. What exists is deteriorating with time (though this machine will last 50-100 years with good maintenance). There is no replacement on hand. Etsy jewelry makers are cannibalizing older, more beautiful machines for their keys. Parts get stripped from a beater to bring a similar model back to working order. If you like to write, a well-tuned manual typewriter is a dying opportunity.

I’ve heard people praise how much more creative they can be on a manual. There are no pop-ups, no internet a click away. The physical nature of the task demands your focus. I’ve already struggled to find the right key pressure, starting out with a weenie stroke from years of computing that barely made an imprint on the page. Every mistake is permanent. You just have to type it again, better. There is no debating the fact that a typewriter is far less-efficient than a word processor. Those who swear by them usually only write a draft or two before keying them into a computer for extensive editing and post-production. I haven’t used it much yet, so I can’t say whether that claim of the tactile nature of creativity is true.

I can’t imagine using it for my main project, Chronicles of the Ancient Sea Kings. The books in this series are clocking in around 360,000 words, nearly 800 pages printed. That might not be a problem, but I have to keep such extensive notes, which change daily as the story moves in accordance with what I call the Wolfram Method of writing, and that adds more characters, pages, inefficiency. I often forget how to spell a Mattaka name, or even what the name was, and have to make liberal use of ctrl+F to remember what I even wrote all those months ago. A typewriter looks like a hopeless proposition.

But J.R.R. Tolkien pecked out The Lord of the Rings on a Hammond 12.

Even if I never use it for the present work, it’s too much fun and money to sit idle. There are other books, other essays, short stories, poetry, angry letters to the editor that may just benefit from a brow-dripping pound session.

My dad collects and restores old lanterns, sometimes well over a century old. He’s revived dozens, maybe a hundred or more. There are people who own and restore as many manual typewriters. I won’t be joining that rank, but my interest doesn’t surprise me. He says he fixes his lanterns to honor the hands that built America—not just in the mechanical sense, but by what fires lit the job site, the home, or the writing desk. That sounds like a solid excuse to buy something that no one seems to need in a technological age. But I note that he finds them indispensable when the lights go out.